The progression of idiopathic scoliosis is related to skeletal growth, peaking during the adolescent growth spurt. Subsequently, once skeletal maturity has been reached, the pathology usually stabilises or slows down.

Knowing the predictors of skeletal maturity allows physicians to predict the risk and timing of curve progression, and therefore choose the most suitable treatment for their patient’s scoliosis.

Several indicators of skeletal maturity are closely linked to the progression of scoliosis. They include chronological age, height and weight, development of secondary sexual characteristics, and menarche.

However, skeletal maturity is known to be the most sensitive indicator of both the speed of skeletal growth and its completion. (1)

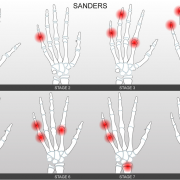

Numerous staging systems for evaluating skeletal maturity, in addition to the Risser sign, have been developed and used in patients with scoliosis. In the scientific community, particularly in the USA, the Sanders staging system is becoming increasingly popular.

Unlike the Risser method, which evaluates the degree of ossification of the iliac crests, the Sanders approach is based on the assessment of the ossification of the epiphyses of the wrist and hand bones, and it divides bone growth into 8 stages. Stage 3 corresponds to the pubertal growth peak when the risk of scoliosis worsening is greatest, while stage 8 corresponds to full skeletal maturity, and thus to the absence of a risk of worsening (in the case of curves measuring less than 50°) (2).

So, what are the pros and cons of this method of assessing skeletal maturity?

PROS:

1. It accurately predicts the skeletal growth peak: the Sanders classification system offers the possibility of dividing the relevant growth periods of patients who are still skeletally immature into multiple categories and would all be grouped as stage 0 using the Risser system. Essentially, some Risser stage 0 patients are at higher risk and more developmentally immature than others who are more skeletally mature but still classified as Risser 0 (1).

2. It more reliably predicts residual growth: the Sanders classification can help doctors to predict residual growth in scoliosis patients more accurately than is possible with other assessment methods, and this allows them to plan better treatment (such as when to “wean” patients off their braces) and better monitor the evolution of the disease. (1)

3. It is a support tool: like other methods, the Sanders staging system, combined with clinical and radiographic parameters, allows doctors to make more informed decisions on the treatment of scoliosis, such as the decision to opt for a conservative approach (based on specific physiotherapeutic exercises and bracing) as opposed surgery, and vice versa (3).

CONS:

1. Its ability to predict skeletal growth may be limited: the Sanders staging system estimates skeletal maturity and residual growth, but it is not 100% accurate and may be limited in its ability to predict this type of growth.

2. It involves radiation exposure: to perform Sanders staging, radiographs have to be taken of the wrist, but this would mean increasing the radiation exposure of young patients, an aspect we always pay close attention to, and something we try to avoid as much as possible. as much as possible. In some places they experimented performing the classical spinal x-rays with specific hand positions to be able to see also the Sanders, but this is still experimental, and we don’t know yet if and how it changes the spinal posture. It could be a solution. In fact, we recommend that our patients have X-rays taken using EOS, a tool that allows their radiation exposure to be reduced. Of course, modern X-rays are nothing like the X-rays of the past, but it is nevertheless always better to have as few as possible.

3. Issues of cost and availability of resources: Sanders staging requires radiographic/logistical resources and specific expertise to interpret the images, which may not always be available in all healthcare settings. Furthermore, using the Sanders system can result in additional costs for patients or for the healthcare system.

Finally, our scientific director, Prof. Stefano Negrini, has explained an important reason why Sanders staging is not currently used at Isico: “We have a very pragmatic approach to the problem, that is based on adding further radiation only if necessary and if it would change our clinical behaviour. The reality is that scoliosis is still highly unpredictable: it can progress unexpectedly at any bone staging or it can stay stable at the highest risk phases. Consequently, the only clinical change when we are at a high-risk phase is seeing the patients more often, and intervening if needed because of progression. Would that change with more precise knowledge of bone maturity? Bone age is correlated with the risk, but not precise enough to rely on that alone – there are too many other unknowns… To explain all this, I often tell my patients that scoliosis treatment is rather like driving a car on a foggy night. We have some significant landmarks, but we never know exactly where we are. Increasing the precision of external reference points may perhaps help us, but it does not take away the fog or the night, which are the two factors that most determine our risk of having an accident, more than the road signs. In other words, we might well manage to obtain a more accurate assessment of the patient’s skeletal growth. Still, if the disease ends up following this indication only partially and behaving in a way we can’t control, then in reality we have not actually obtained any extra information that is really useful for treating our patient. For this reason, we don’t ask patients to have an additional X-ray if it is not really going to change their treatment significantly”.

References

1 – Prediction of Curve Progression in Idiopathic Scoliosis

2 – Maturity Indicators and Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Evaluation of the Sanders Maturity Scale

3 – Managing the Pediatric Spine: Growth Assessment

4 – Is there a skeletal age index that can predict accurate curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? A systematic review