The Risser sign, growth and scoliosis: let’s clear a few things up

When patients come for medical consultations or physiotherapy sessions, numerous measurements get taken and recorded, often without less expert eyes even noticing.

On the other hand, other measurements are quickly seized upon, both by parents and youngsters. Take height, for example. The sliding piece barely has time to touch the patient’s head before the patient, hopeful, blurts out: “Have I grown? Can I leave off my brace now?”

Another milestone we are promptly informed of is menarche in girls, as parents are often convinced that when their daughters start their periods, they have finished growing, meaning that their treatment can come to an end. But this isn’t always the case. On the contrary, this delicate phase can sometimes coincide with the most marked progression of the disease, making it all the more important to act with caution.

Although these are two important examples of the many factors that need to be taken into account to work out what point a youngster’s growth has reached, it has been shown that increases in height and menarche do not necessarily coincide with the individual patient’s growth peak [1] and may therefore not be helpful and/or sufficient when it comes to deciding on the best course of treatment.

Since these manifestations are secondary growth characteristics, they can only be seen as an indication that the patient’s growth spurt has begun. What they do not tell us is precisely how far on it is. There is a scientific explanation for the traditionally held belief that girls “develop earlier” than boys. In fact, because testosterone starts to be released into the body after oestrogens, boys start their pubertal growth spurt later than girls.[1]

To manage scoliosis and optimise the treatment results of the condition, it is crucial to have a good idea of the patient’s residual growth potential and the time remaining until he/she reaches skeletal maturity. An accurate prediction of the growth rate is also required to know when the deformity is likely to be most at risk of progressing. On the other hand, once it has been established with certainty that the patient has finished growing, this is the time at which preventive measures can be stopped with only minimal risk of further deterioration of the curve. [1]

There are various methods we can use to evaluate bone growth in adolescence, and one of them is called the Risser sign.

An individual’s Risser grade can be determined from an anteroposterior X-ray of the spine. An advantage of this method is that the same X-ray can be used to measure both the number of Cobb degrees (necessary to diagnose scoliosis) and the degree of skeletal maturity, thereby limiting the patient’s radiation exposure.

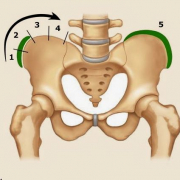

From 0 to 5, Risser grades are assigned based on the amount of calcification present in the iliac apophysis, and the scale thus measures progressive ossification. A Risser grade 0 indicates a low degree of bone maturity: this status is present from birth through puberty.

A Risser grade 5 means that the iliac apophysis has fused to the iliac crest, and the structure is 100% ossified: this status is present in adults [2].

It would be misleading to imagine the transition from Risser 0 to Risser 5 as a continuous and constant progression that occurs over a fixed time and at a set pace. This is because growth is not constant but proceeds at different rates in the different phases. There are times when it pauses, times when it speeds up considerably, and times when it slows down.

The crucial stage in a youngster’s growth, also vital for understanding the course of their scoliosis, is the pubertal growth spurt, during which the disease can alter the shape of the patient’s back in the space of just a few weeks. From the perspective of a Risser evaluation of skeletal maturity, this stage corresponds to the transition from Risser 0 to the complete acquisition of Risser 1.

Between Risser 2 skeletal maturity and the end of the Risser 3 stage, the growth spurt slows down, but as far as the scoliosis treatment is concerned, we still cannot lower our guard: the patient should continue to receive treatment.

Scoliosis treatment is brought to an end gradually as skeletal maturity increases. Once the patient has reached Risser grade 5 (complete skeletal maturity), the treatment can be terminated safely without fearing that some of the hard-won gains might be lost.

The Risser classification varies slightly in different parts of the world, with some differences found, in particular, between Europe and America. In Europe, the successive grades tend to be assigned more cautiously, in the sense that a patient is deemed to have passed from one stage to the next only in the presence of precise levels of bone maturation. On the other hand, the American tendency is to assign the successive grades sooner.

Another method for assessing skeletal maturity is the Sanders classification, whose eight grades are assigned based on the assessment of hand bone growth [3]. Some studies have found the Sanders classification more precise than the Risser sign. It shows higher staging sensitivity when growth is most rapid and is therefore more reliable during certain growth phases [4]. The problem with the Sanders classification is that it requires a separate X-ray of the hand, which therefore means that it could increase the patient’s radiation exposure.

All this information clearly shows that residual growth is essential to evaluate, but at the same time, difficult to establish and interpret.

Specialists can, of course, use the classification they prefer, which will be the one that, in their experience, works best for identifying and evaluating the growth peak in adolescence. It is essential that they can correctly interpret all the data they collect, including from radiographs and patients themselves, to optimise the timing and results of the treatment.

References

[1] Cheung JPY, Luk KD. Managing the Pediatric Spine: Growth Assessment. Asian Spine J. 2017 Oct;11(5):804-816. doi: 10.4184/asj.2017.11.5.804. Epub 2017 Oct 11. PMID: 29093792; PMCID: PMC5662865.

[2] Greiner KA. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: radiologic decision-making. Am Fam Physician. 2002 May 1;65(9):1817-22. PMID: 12018804.

[3] Sanders JO, Khoury JG, Kishan S, Browne RH, Mooney JF 3rd, Arnold KD, McConnell SJ, Bauman JA, Finegold DN. Predicting scoliosis progression from skeletal maturity: a simplified classification during adolescence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008 Mar;90(3):540-53. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00004. PMID: 18310704.

[4] Minkara A, Bainton N, Tanaka M, Kung J, DeAllie C, Khaleel A, Matsumoto H, Vitale M, Roye B. High Risk of Mismatch Between Sanders and Risser Staging in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Are We Guiding Treatment Using the Wrong Classification? J Pediatr Orthop. 2020 Feb;40(2):60-64. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001135. PMID: 31923164.