Scoliosis and posture: the two go hand in hand

Let us start with one thing we know for sure: idiopathic scoliosis is not a postural complaint, but rather a progressive spinal disorder that causes three-dimensional deformation of the vertebrae.

Although it is still not clear exactly why scoliosis occurs, its progression is known to be due, in part, to the force of gravity (i.e., the force of gravity does not cause the disorder, it simply helps it to progress).

Let us try to explain this in simple terms: our spine is like a tower of building bricks that serves to support us, and the bricks distribute evenly the weight it has to bear. If we have scoliosis, some of our bricks are not correctly shaped.

As a result, they are not properly aligned and our tower (spine) may have curve(s) in it. A spine with curve(s) is no longer able to distribute evenly the weight it has to bear; indeed, this presses down harder on the inside of the scoliotic curve, and less on its outside.

If our spine is well supported, this effect can be lessened, because the support allows the blocks to realign, and this, in turn, reduces the extent of the curve(s). Conversely, without support, the bricks will slide even further to one side, increasing the angle of curvature and shortening the trunk even more.

What does all this mean? That our scoliotic curve will worsen more rapidly unless we continually correct it.

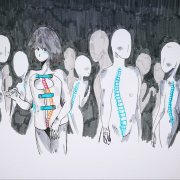

This is why the exercise-based treatment method used at Isico is based on the principle of SELF-CORRECTION: affected youngsters learn to intervene independently to control and align their spine as correctly as possible, thereby countering its tendency to collapse in the direction of the scoliotic curve.

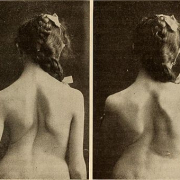

Let us consider another aspect. On a spinal X-ray, we can measure the degrees of curvature present. The angle of curvature is actually the sum of two components: the deformity itself and the effect of postural sagging in the direction of the curve. The contribution of this second component is largely dependent on our capacity for “self-correction”.

How can we distinguish between these two components, i.e., actual bone deformity and postural sagging, so as to be able to intervene effectively on each of them? Again, on an X-ray, but in this case, it must be taken with the patient lying down, so that the degrees of curvature caused by postural sagging disappear, and all that can be seen, and measured, are those due to the deformity itself.

One study, now rather old but still valid, published in Spine in 1976 (Standing and supine Cobb measures in girls with idiopathic scoliosis, G Torell, A Nachemson, K Haderspeck-Grib, A Schultz), showed that postural sagging in scoliosis causes, on average, 9 degrees of curvature (ranging from 0 to a maximum of 20), and that the degrees attributable to postural failure are independent of the severity of the curve. Another interesting study published in Spine, in this case in 1993 (Diurnal variation of Cobb angle measurement in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, M Beauchamp, H Labelle, G Grimard, C Stanciu, B Poitras, J Dansereau), shows that back “fatigue” can also affect the Cobb angle. In this study, youngsters with moderate to severe scoliosis (an average of 60 Cobb degrees) were X-rayed in the morning and then in the evening. The X-ray taken in the evening showed an average 5-degree increase in curve severity.

What should we do in treatment terms? Clearly, exercises alone cannot alter the actual bone deformity resulting from the scoliosis, which needs to be treated with a combination of exercises and brace wearing.

Nevertheless, specific exercises and self-correction can do a lot to address the problem of postural sagging. And if this “sagging” is responsible for an increased Cobb angle, we need to work hard at our exercises in order to “eat away” at (reduce) the part of the curve that is due to this component.