Scoliosis: why appearance matters

To treat scoliosis solely on the basis of radiological images, assessing only the patient’s skeletal conditions, would be a huge mistake.

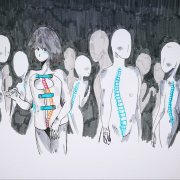

The evolution of scoliosis typically leads to spinal changes in the three planes of space, and it therefore causes a modification of the ribcage. Indeed, as scoliosis progresses, it also changes the appearance of the torso, and this, depending on the severity of the curve, can impact more or less markedly the patient’s appearance.

According to the international guidelines on the conservative approach to scoliosis drawn up by Sosort, improving the patient’s appearance is the second most important goal of treatment.

If the condition is not adequately treated, or the treatment is ineffective, the above-mentioned changes will become more and more marked, even to the point of severely impairing the patient’s quality of life.

The way we see our body is highly subjective. People with asymmetries of the hips or shoulder blades, or a hump, react differently to the problem, in the sense that a defect that one person hardly thinks about, may be quite unbearable to another.

“In treating scoliosis, we must be careful not to overlook this question of aesthetics, precisely because we can never assume that our patients see things the same way as we do: any asymmetry, be it major or minor, can have a considerable psychological impact – says dr Irene Ferrario, Isico Psychologist – It is also important to remember that these changes occur in a period – adolescence – that is already full of challenges, and can sometimes see youngsters struggling to build, and accept, their own body image”.

For all these reasons, addressing patients’ aesthetic concerns should not be seen as indulging them; indeed, correcting aesthetic defects is not of secondary importance compared with correcting the curve: it is a therapeutic necessity. When a patient has, for example, one flank straighter than the other, a misaligned shoulder blade, or a hump that alters the line of the upper body, these changes may be perceived as more or less visible, depending both on the individual’s relationship with his/her body, and on his/her own (entirely subjective) aesthetic parameters. Over time, however, if the disease progresses, these changes can become objectively visible and psychologically damaging.

Obviously, we are referring here to the most severe cases, but these remarks nevertheless serve to illustrate that a scoliosis treatment plan cannot exclude the issue of aesthetics. Addressing this aspect is a necessary part of the treatment.

In short, good conservative practice absolutely must take into account aesthetic considerations. Regardless of whether or not the patient highlights this aspect, considering it to be of primary importance, the physician should in any case include it as a key objective of the treatment, which may contribute to its success.

In our care pathway, it is often the parents who first “raise the alarm”, alerting the therapeutic team to these concerns. This is because they are often the first to notice changes in the child’s body, especially if he or she is still too young to have a real awareness of his/her body and body shape.

Sometimes, these “alarm bells” are justified, and sometimes not, given that mild bodily asymmetries are normal, and do not always indicate an underlying problem. Purely aesthetic concerns, especially when raised by our young patients, should never be dismissed. Identifying and acknowledging a patient’s experiences and feelings is crucial to their all-round care.

“Another aspect that should be underlined is brace wearing, as this treatment (when required) also has aesthetic implications –explains Lorenza Vallini, Isico PT – Many patients worry that their brace can be seen under their clothing, and addressing this concern is an important part of increasing the acceptability of the treatment: fitting patients with increasingly thin braces, moulded to their shape and therefore “almost invisible” to the onlooker, has proved to be a key factor in reducing and containing the deformity. Moreover, a good brace produces a truly remarkable aesthetic correction, not only immediately but also in the long term“.

Indeed, the brace wearer is rewarded with an improvement that lasts into adulthood. But arguments based on the long-term advantages are often lost on youngsters, and therefore an “invisible” brace is still crucial.

The main objective of the treatment will always be a well-balanced and harmonious body, which is as symmetrical as possible. After all, no one is perfect, not even Botticelli’s Venus. Indeed, her imperfections are part of her beauty!