Isico at the SRS 56th Annual Meeting

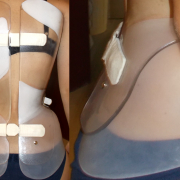

The SRS 56th Annual Meeting, running from 22 to 25 September, 2021, was a hybrid event that included a robust in-person programme live in Missouri, USA and a virtual component, to allow delegates who were unable to attend in person to follow and enjoy the event. Isico took part with a podium presentation of its research “The natural history of adults with spinal deformities: results from a prospective collection of radiographic data”, given by dr. Sabrina Donzelli (Isico physiatrist) and a poster presentation, by Prof. Stefano Negrini (scientific director of Isico), entitled “Reducing Pelvis Constriction Changes the Sagittal Plane. A Retrospective Case-Control Study of 37 Free Pelvis vs 451 Classical Consecutive Very-Rigid Sforzesco Braces”.

The Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) Annual Meeting is a forum for the realization of the Society’s mission and goals, the improvement of patient care for those with spinal deformities. Nine faculty-led instructional course lectures, case discussions, and 180 abstract papers were presented on an array of topics.

The Isico research started from current data telling us that scoliosis also affects adults and that patients with scoliosis treated during growth should have their backs regularly monitored in adulthood. This applies particularly to those with curves that measured more than 30 Cobb degrees when they finished growing. Curves measuring more than 50 degrees, on the other hand, are at high risk of worsening, and in these cases, therefore, surgical treatment is indicated.

This is what we know, but do we know whether there are any particular times or ages at which the risk increases? Are there any conditions that might be associated with the risk of worsening?

“No one has ever investigated the factors that determine progression of the disease” explains Dr Donzelli, “because long-term monitoring of patients is a costly process. On the other hand, knowing when it is really necessary to increase the frequency of checks would allow timely interventions and therefore help to reduce costs. In our retrospective longitudinal study, we analysed the factors involved in the progression of scoliosis.”

The Isico researchers began by collecting data from radiographs the patients had undergone over the years. They measured these radiographs and, for each patient, plotted curves showing scoliosis worsening over time. In all, 767 patients (mean age 35 years, 85% women) met the inclusion criteria and were able to provide at least two X-rays taken in adulthood and at least 5 years apart.

The authors then analysed which of the following factors influenced changes in Cobb degrees over time:

- Gender (F or M)

- Idiopathic diagnosis (yes/no)

- Menopause (yes/no)

- Thoracic localisation (yes/no)

- Comorbidities: bone metabolic diseases, bone and joint inflammatory disease, neurological associated disease (yes/no)

- Brace during growth (yes/no)

- Back pain (yes/no)

- Family history of spine deformities (yes/no)

- BMI at baseline (continuous)

The results of the research showed age to be one of the main predictors of worsening: after the age of 50, the risk of worsening increases, therefore from this age it is a good idea to start having more frequent check-ups; moreover, the forms of scoliosis seen in adults are different, and the period of time over which scoliosis appears and then progresses is much longer.

“There are numerous factors involved, and research in this field is still in its infancy,” concludes Dr Donzelli. “The lengthy monitoring times and the very small variations occurring over time make it particularly complicated. Systematic data collection and regular monitoring over time are essential not only for research purposes, but above all to ensure timely preventive intervention.”