Is Life Turning You Kyphotic? Here’s How to Prevent It

The spine supports the torso and allows the head to stay upright, keeping the gaze towards the horizon. Proper alignment in the sagittal plane helps maintain the torso in the correct position with minimal energy expenditure and optimal load distribution along the spine.

Over time, particularly in older adults, a forward imbalance tends to develop, causing the torso to lean forward. Researchers have identified the age range of 50 to 60 as the period when this imbalance typically begins to manifest, progressively worsening with age. Compensatory mechanisms then come into play, creating a vicious cycle involving the pelvis and the entire spine, leading to specific degenerative changes.

The pelvis tilts backwards, lumbar lordosis decreases, and the upper torso bends forward. In some cases, these changes in sagittal alignment occur rapidly and progressively, developing into pathological conditions.

Certain factors may exacerbate this, such as the presence of scoliosis, disc disorders leading to reduced lordosis, or stiffness in the spine. Severe kyphosis or kyphosis resulting from vertebral fractures also contributes to forward collapse, as does weakness in the spinal extensor muscles, leading to forward lean.

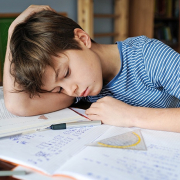

Now, let’s consider our daily activities.

Most of what we do involves looking downward or at least keeping the head tilted forward. For example, how much strain is placed on the cervical vertebrae when the head is tilted forward at 30 degrees? (Remember that we usually tilt our heads much more than 30 degrees when we look at our phones.)

At this angle, the discs experience 400% more stress than when the head is upright and looking forward. The natural tendency towards forward collapse, combined with daily activities that increasingly involve static, flexed postures and potential degenerative spinal conditions, accelerates the forward tilt of the torso. This forward imbalance results in pain, reduced spinal functionality, fatigue, aesthetic concerns, and, most importantly, a decline in quality of life.

What Can We Do?

- Resist Gravity: Throughout the day, whether standing or sitting, try to sit or stand up straight and hold this position for a few seconds.

- Engage in Regular Physical Activity: Any exercise is beneficial, but activities that engage the trunk extensor muscles are especially helpful. Don’t stop moving! It’s also a good idea to vary your exercises over time, which will benefit your back as well.

- Seek Medical Advice: If you notice yourself leaning forward when tired, especially in the evening, or if those around you point out that you’re becoming more stooped, it’s time to seek a medical evaluation.

…And if life pushes us forward? Let’s straighten it out!