Many people are saying that the present coronavirus epidemic will change our whole way of being: our relations with others and the way we see things. Indeed, this health emergency has forced practically all of us to change our habits and our way of life.

Perhaps we should therefore also be asking ourselves whether, in the post-Covid age, there will be greater recognition of the health sector and a greater understanding of the importance of the scientific community, research and evidence-based investigations.

Just think about it. Today, we are all anxiously waiting for an anti-Covid vaccine, whereas not so long ago (although it feels like a lifetime) there were parents who were choosing not to vaccinate their children with drugs that have been available on the market for many years and that countless studies have shown to be effective.

It is to be hoped that, in the wake of this emergency, it will be clear to everyone that infectious diseases (i.e. diseases that are passed from person to person) are only truly brought under control when most of the population is immune to them, in other words when there is so-called herd immunity. This situation is reached when a large section of the population has either been vaccinated against the disease or exposed to the virus and developed antibodies against it.

Unfortunately, there is plenty of incorrect information circulating at the moment. This includes, on a medical level, numerous false beliefs and myths that are difficult to eliminate. These ideas are spread in different ways: via media channels, by word of mouth or even, in some cases, by poorly informed healthcare workers. Some of the ideas going around might raise a smile, but what is less amusing is that they are sometimes heeded and applied by people without the necessary education and expertise to recognise them for what they are.

The Italian Health Ministry has warned people to beware of the various fake news currently circulating about novel coronavirus infection, debunking myths concerning Ayurvedic therapies, yoga and breathing exercises — these are claimed to offer protection against the virus —, the idea that it can be sweated out of the body during physical exercise, and even the claim that honey exerts a useful antibacterial and disinfectant action.

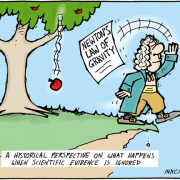

There is a common saying used in science: “In God we trust, all others must bring evidence”. Because what assumes scientific validity must first be proven.

The basis of all evidence-based medicine is the same: scientific studies in which data have been collected and methods and results rigorously compared and analysed by the various experts on the topic in question. A good doctor must always seek to integrate the best scientific evidence from research with the patient’s clinical experience and values. Patients, in turn, must be fully informed about the treatments they are about to undertake.

But the trouble is, many people today tend to lack scientific culture, and few really appreciate the value of “scientific evidence”. Simply trusting in the views of a certain doctor, or the experiences of someone we know, is really no way to drive advances in medicine.

In rehabilitation, as in other branches of medicine, there exist various methods and techniques whose efficacy has been little explored, and others that have no valid medical basis and are quite often administered by people without proper qualifications, who therefore lack the right approach.

For example, numerous studies have shown that simply telling patients “what a terrible back you have!” will only aggravate their tendency to catastrophise and increase their fear of movement, two factors that contribute to the chronification of back pain.

Similarly, reading on an MRI report that your spine has several protrusions or thinned discs is no more significant than being told that you have lots of grey hairs: the fact that you have a hernia is meaningless unless this information is correctly set within the overall clinical context. What we are saying is that it is the medical specialist’s job to make the diagnosis and prescribe a course of rehabilitation, which the therapist then decides how best to implement in the individual patient.

In the literature, there are various studies showing that some subjects with spinal hernias are completely asymptomatic. Unfortunately, however, we still have patients who come to us either alarmed to have learned they have a hernia or convinced that their osteopath, by manipulating their spine, has managed to “put back” a decades-old hernia.

At ISICO, we treat disorders of the spine, a field closely related to the concept of posture. Postural problems, too, are frequently addressed using approaches whose effectiveness may not have been properly demonstrated.

While this does not always create problems, in some cases, it costs patients valuable time and money, delaying the reaching of a correct diagnosis and proper planning of their care.

Take scoliosis, for example, a condition that tends to worsen with growth: it is one thing starting the treatment when the patient has a curve measuring 20°, quite another waiting until it has reached 40°. The treatment options, by this stage, are drastically reduced, and there is the risk of having to resort to more invasive therapies. Clearly, it is a shame for this situation to have been reached simply because an appropriate treatment was not proposed sooner.

At the courses we run, we are often asked, both by patients and colleagues, whether there is any link between scoliosis and mastication, dental occlusion, and foot and/or knee position/alignment. For the moment, all these ideas are theories with no scientific basis. It could be that, in the future, data will be collected that confirm these correlations and we will be prompted to review our position, but as things stand, it is not ethical to propose treatments based on these theories.

As regards the treatment of scoliosis, the current scientific literature tells us that we have different avenues that we can pursue: observation, exercises, bracing (with different types of brace, for different numbers of hours per day) and, in the most severe cases, surgery.

It is crucially important to offer the patient the right treatment, where “right” means that it is supported by scientific evidence of its effectiveness. Specific exercises for the back, including self-correction ones, are an active and important part of scoliosis treatment, as well as scientifically proven to be effective (“Specific exercises reduce the need for bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: a practical clinical trial“). Instead, gymnastics generally, like other physical activity, has no therapeutic value, even though it can have positive effects (“Sport activity reduces the risk of progression and bracing: an observational study of 511 JIS and AIS Risser 0-2 adolescents“).