Adults: can hyperkyphosis be improved?

With the passing years, many adults start to realise, when they look at themselves in the mirror, that they are getting increasingly stooped. Some people are unwilling to accept this situation and start wondering whether they can do anything to arrest this process. The question is, can this condition be improved or is it pointless even to try?

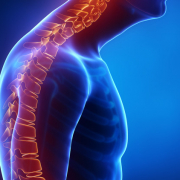

The condition we are talking about is HYPERKYPHOSIS. If you look at a person sideways on, you see that their back is not straight, but has natural curves, whose function is to cushion the forces that act on the spine. Following the back line from the top down, we see that first, at cervical level, there is a forward curvature, termed LORDOSIS, then a backward dorsal one, called KYPHOSIS, followed by another forward curve, at lumbar level, also called LORDOSIS. When the amplitude of the dorsal kyphotic curve, measured on an X-ray, exceeds the normal range, we speak of HYPERKYPHOSIS. Usually, this curve measures between 20 and 60 Cobb degrees.

Various factors explain this considerable range. Some are positional and related to the type of examination performed (for example the position of the arms), while others are linked to the associated disorder itself, which may be characterised by marked (e.g., scoliosis) or more prominent (e.g., idiopathic hyperkyphosis, Scheuermann’s disease) curves. Elderly people often present hyperkyphosis caused by the osteoporotic vertebral collapse. As the bones become more fragile, even minor movements can cause tiny fractures of the anterior portion of the vertebrae, resulting in progressive bending of the whole back.

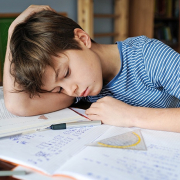

Everyone’s back bends forward more as the years go by, regardless of whether or not they have hyperkyphosis.

Why is this? Most people spend much of their time, i.e., many hours of most days over many years, in a hunched position, with the head looking downwards. In fact, in our daily lives, we are often in the sitting position, which encourages forward flexion of the back; furthermore, many of the activities that require us to move around (cooking, cleaning, DIY, hobbies) also involve bending forwards. For all these reasons, dorsal kyphotic curves tend to get progressively worse over time, we become increasingly stiff, and the trunk extensor muscles grow weaker, resulting in postural collapse. In short, all these factors, combined, leave us “crushed” by the force of gravity.

What are the effects of hyperkyphosis? In adults and the elderly, hyperkyphosis can increase our risk of back pain and worsen our quality of life as we find it increasingly challenging to support our back, both when seated and when standing. Another effect is impaired balance and stability when walking.

So, to go back to our original question: is it possible to break this vicious cycle through physiotherapy and, in particular, through specific exercises?

The answer is yes! The initial objectives of the treatment are to reduce the stiffness of the dorsal spine and strengthen the trunk muscles that oppose the force of gravity, so as to facilitate postural recovery, and to integrate the correction into daily life. Indeed, from the outset, the treatment approach based on specific exercises encourages patients to learn the crucial “self-correction” movement that allows them to achieve optimal realignment of the spine in the sagittal plane without compensating for this at other levels of the spine (reference: Exercise for improving age-related hyperkyphosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis with GRADE assessment. Ponzano M, Tibert N, Bansal S, Katzman W, Giangregorio L. Arch Osteoporos. 2021 Sep 21;16(1):140. doi: 10.1007/s11657-021-00998-3. PMID: 34546447)

.

Once the improvement has been obtained, it needs to be made stable and lasting. This involves reducing the frequency of the specific exercises and integrating them with other types of physical or sporting activity, all the time continuing to maintain the correction in daily life.

Together, all this translates into less pain, better physical function and a more attractive back.