Brace adherence Influenced by geographic and personal factors: ISICO study published in children

The ISICO study entitled “Geographic, Personal and Clinical Factors Influencing Brace Adherence in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis” has just been published in the journal Children (MDPI). The research also competed for the SOSORT Award 2025.

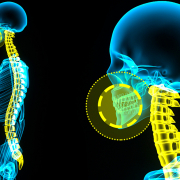

Brace therapy is an effective treatment for adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), provided that adherence is high. While previous studies have objectively measured compliance using thermal sensors, the influence of geographic and socioeconomic variables—such as living in mountain versus seaside areas, in large cities versus small towns, or differences in income level—had not previously been investigated.

The study, led by Alessandra Negrini, physiotherapist at ISICO and author of the research, analyzed 1,904 adolescents(mean age 13 years; mean curve 35° Cobb). Adherence was measured using a thermal sensor (iButton) applied to the brace. The variables examined included age, prescribed brace-wearing hours, geographic area (Northern, Central, Southern Italy), gender, skeletal maturity (Risser), curve type, presence of back pain, income level, altitude above sea level, and distance from the sea.

Key Findings

- 90% of patients demonstrated good adherence (wearing the brace for more than 75% of the prescribed hours).

- Higher adherence was associated with:

- Younger age

- Female gender

- A prescription of more than 20 hours per day

- Residence in Northern Italy

The results suggest that climatic and social factors may influence treatment adherence.

As Alessandra Negrini comments:

“Through this study, we aimed to verify the influence of geographic, personal, and clinical variables — routinely recorded by doctors — on adherence to brace treatment. Understanding that certain factors can reduce adherence allows us to identify patients who may benefit from targeted strategies to improve compliance. Thanks to this type of research, we can enhance the personalization of therapeutic interventions, adapting them to patient characteristics to maximize treatment effectiveness.”

📖 The full article is available here