Full-time treatment: no stress!

We talk of “full-time treatment” whenever a brace needs to be worn round (or almost round) the clock, i.e., for 23 or 24 hours a day. When patients with scoliosis are treated using a brace, it is not unusual to have to wear the device full time in order to effectively address severe curves (those measuring more than 40 Cobb degrees) or high-risk situations (a pubertal growth spurt).

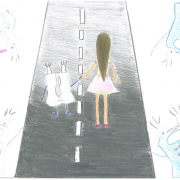

Full-time treatment is a tough challenge, especially if you consider that it usually begins at between 11 and 15 years of age, in other words, just before or during adolescence, which is a notoriously tricky time that already brings plenty of changes. Youngsters of this age no longer see the world through children’s eyes. Instead, they begin to experience all kinds of doubts and insecurities, and sometimes they are unhappy about the changes in their appearance, or about having to wear dental braces or glasses. It is therefore entirely understandable that being prescribed bracing treatment can be upsetting for them, and also for their parents who would do anything to spare their child any suffering.

In the literature, it is suggested that the start of bracing treatment (the first 6 months) can negatively affect the patient’s quality of life.

Even though there is no scientific proof of this — on the contrary, research tells us that treatment, ultimately, does not negatively impact quality of life —, there can be no denying that the early stage of bracing is hard and must be overcome. In particular, it is crucial to avoid poor adherence to the treatment that might potentially lead to its early and total abandonment and thus expose the patient to all the risks, in terms of progression and consequent severity of the condition, that are associated with scoliosis in childhood and adolescence.

“This is a very important issue for us at Isico”, remarks physiotherapist Lorenza Vallini. “We have long been aware of the difficulties youngsters face at the start of this experience, which we liken to a marathon rather than a sprint: our youngsters have to get to the finish line on their own two feet, but we healthcare professionals are alongside them all the way, guiding and helping them and their families.”

And what about friends? Well, friends are like fans on the terraces; if they feel involved, they will cheer the patient on.

All this is perhaps easy for us to say because the fact is that when full-time bracing is prescribed, which means 23 or even 24 hours a day, the patient can feel like their world is falling apart. That is why we at Isico like to make sure we always have a chat with the family and the youngster after their appointment.

“We know very well that this is a key moment, a watershed moment that needs to be addressed together”, Vallini continues. “Our therapists are trained to listen to doubts, answer a thousand questions, and provide all the necessary explanations. We try to get the youngsters involved, showing them videos of other young “brace wearers” doing all kinds of everyday activities, including sports, with their brace on. They are often visibly surprised to see their counterparts happily taking a dip in the sea or swimming pool.”

It is also important not to overlook the aesthetics of brace-wearing!

We at Isico are always careful never to overlook the aesthetic aspect. Many of our patients are girls who are of an age at which comparing yourself with others is a normal part of growing up: “We always stress that braces are hardly visible under clothes, and we give patients tips and advice about their appearance”, Vallini says. “This moment is an opportunity to start building an alliance with the patient. Obviously, our work and involvement don’t end with that one chat, which on the contrary is the starting point for a process that will continue over the monthly sessions we have with these youngsters thereafter. The first session after delivery of the brace is particularly important, as it is when we try to present this “intruder” as a friend, not the easiest to be sure, but a friend nonetheless.”

That is why this particular session is designed to be motivating as well as technical, an opportunity to tackle any issues or doubts that have arisen and gather the patient’s reactions – both the tears and the laughter.

As soon as the brace arrives, it is tested by an Isico doctor, who provides a series of explanations in order to get the treatment off to a good start. As a rule, whenever possible, a meeting with the therapist is also arranged so that youngsters are not left to face their fears and doubts alone. When this is not possible, a telephone contact is offered and, after the first session, the patient is also contacted by email to find out if there have been any difficulties.

Availability, care and assistance are the cornerstones of our approach: “We never underestimate any request, from the simplest to the most complicated”, Vallini says. “We make sure patients realise we are always there for them, as we want them to be reassured that there is always someone available for them.”

The importance of listening

The Isico team includes all the specialists necessary to support and monitor young brace wearers, so not only doctors and orthopaedic technicians, but also therapists and a psychologist (who sees patients directly on the rare occasions when this is felt to be necessary, but usually intervenes through the other professionals). All the team members will accompany the patient for a part of their journey, to support them and ensure that the therapy is going as it should, particularly at the start.

Will there be any other particular crisis moments? Undoubtedly! In the course of a long and demanding treatment process, undertaken in the midst of a thousand other emotional interferences from the outside, this is only to be expected: “The main thing for us is to remain vigilant so that we know when a family might be needing extra help”, Vallini says. “Everyone is ready to add the right input at the right time to help patients reach the finish line. And when they do, the smiles and hugs we get from them are quite wonderful, as is their tangible sense of pride”.